Search Database

The Easter Rising 1916

The Easter Rising of 1916 was a pivotal episode in Irish history. It led to a series of events that transformed the political landscape and brought about the conditions for a War of Independence three years later. That conflict resulted in the establishment of this state.

Background and planning

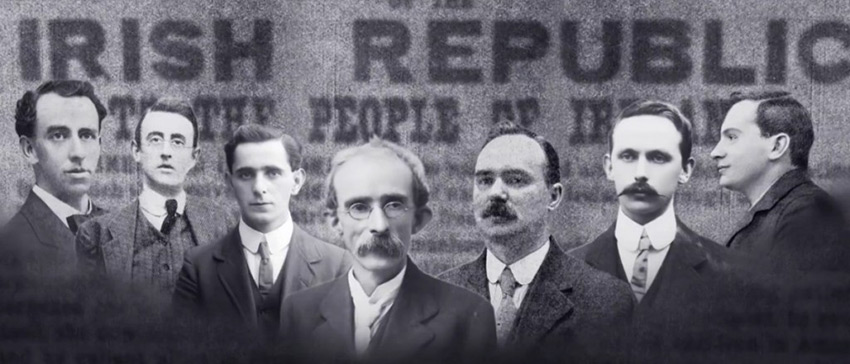

The Rising was planned by a small group of members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), which was known as the Military Committee or Military Council. It was established in 1915 and by early 1916 it comprised the seven men who would sign the Proclamation of the Irish Republic: Thomas Clarke, Seán MacDiarmada, Patrick Pearse, James Connolly, Thomas MacDonagh, Eamonn Ceannt and Joseph Mary Plunkett.

Left to right: Thomas MacDonagh, Joseph Mary Plunkett, Seán MacDiarmada, Thomas Clarke, James Connolly,

Eamonn Ceannt and Patrick Pearse

The Rising was planned in the context of the shelving of Home Rule due to the outbreak of war in 1914. In the period 1912-14, Home Rule dominated Irish politics. The Third Home Rule Bill was passed by parliament in 1914 and would have given Ireland control over internal affairs while it remained within the United Kingdom. However, it was bitterly opposed by Unionists and in 1912, they founded the Ulster Volunteer Force. The Irish Volunteers were founded the following year to uphold Ireland’s rights, including the right to have Home Rule. Tensions rose as both forces recruited and drilled.

Home Rule finally passed through parliament in May 1914 and in July, there was a last-ditch effort to achieve agreement on the issue at the Buckingham Palace Conference, called by King George V. However, it failed. Then on 4 August, Britain declared war on Germany and soon after, it was agreed that Home Rule would be ‘shelved’ until after the war. Thus, the outbreak of a European war may have averted a war in Ireland.

When, in September, John Redmond pledged support for Britain’s war effort, the Volunteers split. It is estimated that about 180,000 supported Redmond, with 11,000, led by Eoin MacNeill, refusing to do so. The latter continued to call themselves ‘Irish Volunteers’ and the Redmondite majority became ‘Irish National Volunteers’.

The postponement of Home Rule led the IRB to conclude that the time had come for a rebellion against British rule. In the context of the war, it looked to Germany for help on the basis that ‘my enemy’s enemy is my friend’. Sir Roger Casement, a distinguished diplomat who became an ardent nationalist, was sent to Germany in late 1914 to appeal for help. He tried unsuccessfully to raise an Irish brigade from amongst Irish men who were taken as prisoners-of-war while serving in the British forces.

The aim of the Military Council was to use the Irish Volunteers as the main force in the planned rising. The organisers intended the rising to begin at Easter when there were manoeuvres by the Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army planned. However, the Volunteer chief of staff, Eoin MacNeill was not informed of this because of his opposition to taking offensive action.

Confusion and countermand

Roger Casement’s mission to Germany had very limited success. However, he was given about 20,000 obsolete rifles which were placed on a ship, the Aud, and dispatched to Ireland on 10 April. Casement and two companions travelled on a submarine on 15 April. They came ashore at Banna Strand, County Kerry on Good Friday, 21 April and all three were soon arrested. The Aud was tracked by British vessels and on 22 April after they intercepted it, its captain, Karl Spindler, scuttled the ship rather than allow it to be captured.

Meanwhile, Eoin MacNeill had been won over to supporting a rebellion – at least very briefly. This was due to the appearance of a document purporting to reveal that the authorities planned to arrest leaders of the Volunteers and other nationalist organisations and occupy their offices. This so-called ‘Castle Document’ was based on one smuggled out of Dublin Castle, but it had been altered to make it seem that the crack-down was imminent. When MacNeill realised that the manoeuvres on Easter Sunday were to be the start of the rising, he moved to prevent it. He was then told of the impending arrival of German arms and changed his mind, believing that sufficient weapons would give the Volunteers the potential for success. However, on Saturday evening, the chief of staff learned that the guns were lost and the ‘Castle Document’ was a forgery. MacNeill then issued a countermanding order and had it sent to Volunteer units throughout the country and published in the Irish Independent.

Despite this huge blow, the Military Council decided to go ahead with action on Easter Monday. The countermand and the lack of time to contradict it meant that in reality, the units most likely to mobilise were those in the Dublin area.

The Rising

There are no surviving plans for the rising and it is difficult to be certain about the overall strategy the organisers had. The available evidence suggests that the River Shannon was seen as a key defensive line, with a concentration of insurgents in the west, boosted by German support arriving on the west coast. The rising in Dublin would involve the occupation of several major buildings and locations, both public and private.

On Easter Monday morning, 24 April, members of the Volunteers, Cumann na mBan, the Irish Citizen Army and some smaller organisations moved into positions in the city. The headquarters were set up in the General Post Office and shortly after noon, Patrick Pearse emerged from the building and read the Proclamation of the Irish Republic. Pearse, a writer and teacher, was in effect the leader of the rising, though he was not a military man. Amongst the others in the GPO were Thomas Clarke, James Connolly (leader of the Irish Citizen Army), Seán MacDiarmada, Joseph Mary Plunkett (credited with much of the planning of the rising) and some who would later become famous like Michael Collins (Plunkett’s aide-de-camp), Desmond Fitzgerald and Seán Lemass.

On Easter Monday morning, 24 April, members of the Volunteers, Cumann na mBan, the Irish Citizen Army and some smaller organisations moved into positions in the city. The headquarters were set up in the General Post Office and shortly after noon, Patrick Pearse emerged from the building and read the Proclamation of the Irish Republic. Pearse, a writer and teacher, was in effect the leader of the rising, though he was not a military man. Amongst the others in the GPO were Thomas Clarke, James Connolly (leader of the Irish Citizen Army), Seán MacDiarmada, Joseph Mary Plunkett (credited with much of the planning of the rising) and some who would later become famous like Michael Collins (Plunkett’s aide-de-camp), Desmond Fitzgerald and Seán Lemass.

The other garrisons were as follows:

- The Four Courts (1st battalion, Dublin Volunteers), commanded by Edward Daly, brother-in-law of Tom Clarke;

- Jacob’s Biscuit Factory (2nd battalion), commanded by Thomas MacDonagh;

- Boland’s Mill (3rd battalion), commanded by Eamon de Valera;

- The South Dublin Union, a workhouse (now St James’s Hospital) (4th battalion), commanded by Eamon Ceannt.

In each case, there were outposts which meant in effect that a garrison controlled an area of the city.

Additionally, there were two garrisons dominated by Irish Citizen Army members. One, commanded by Seán Connolly set out to attack Dublin Castle on Monday morning. After a skirmish at the gates, the unit occupied near-by City Hall, where Connolly was killed that afternoon. The building proved to be an untenable position and was vacated within twenty-four hours.

The other ICA unit was commanded by Michael Mallin, with Countess Constance Markievicz second-in-command. It occupied St Stephen’s Green, again a poor choice as a defensive post due to the fact that it was overlooked by the Shelbourne Hotel and other buildings. The garrison withdrew to the Royal College of Surgeons on Tuesday.

The place outside Dublin that had the most significant fighting was Ashbourne, County Meath, where Thomas Ashe led the 5th battalion of the Dublin Volunteers (later known as the Fingal Brigade). It captured the Royal Irish Constabulary barracks in Ashbourne.

Otherwise, there were two places where large numbers of Volunteers mobilised: Wexford and Galway. Volunteers occupied the Athenaeum Theatre in Enniscorthy on Thursday and initially intended to march towards Dublin. However, only a small unit did, but it turned back. In Galway, a large force of at least 500 Volunteers, led by Liam Mellows, mobilised in the Athenry area. They remained in situ until the end of the week and did not take offensive action.

The Rising in brief

Monday, 24 April: members of the Volunteers, the Irish Citizen Army and Cumann na mBan occupied key buildings in Dublin. Patrick Pearse read the Proclamation of the Irish Republic at the GPO.

Tuesday, 25 April: British re-enforcements began arriving in Dublin.

Wednesday, 26 April: the gunboat Helga sailed up the Liffey and began shelling Liberty Hall. The Sherwood Foresters, a British regiment, were ambushed at Mount Street Bridge by members of Eamon de Valera’s battalion in one of the bloodiest episodes of the week.

Thursday, 27 April: James Connolly was wounded in the GPO.

Friday, 28 April: General John Maxwell arrived to take charge of suppressing the rising. The leaders evacuated the GPO and occupied a building on Moore Street. They planned to go to the Four Courts to make a final stand.

Saturday, 29 April: Pearse agreed to surrender unconditionally.

Sunday, 30 April: other garrisons surrendered once they had verified Pearse’s order.

Executions and imprisonments

As soon as hostilities ceased, there were large-scale arrests and detentions. There were just over 3500 people taken in, including seventy-seven women who were held in Richmond Barracks, Inchicore. Of the overall number of men arrested, 1424 were released within a fortnight.

Fifteen men were executed, beginning on 3 May, including the seven signatories of the proclamation and some other leaders. One of the fifteen was Thomas Kent, who was shot in Cork. The final execution was that of Roger Casement, who was hanged in Pentonville Prison, London, on 3 August, having been convicted of high treason.

There were raids and arrests in Longford in May. Frank McGuinness and Tom Bannon were arrested soon after they returned from Dublin and sent back to the city. Joe Callaghan, Longford town, was sent to Dublin for trial but returned home after being acquitted of involvement. Hubert Wilson of Keon Terrace, Longford, a member of the IRB and the Volunteers, was arrested. So too were John Cawley and Paul Cusack from Granard, who had travelled to Dublin with Larry Kiernan on Tuesday, 26 April, to try to obtain orders, but without success. Wilson, Cawley and Cusack were sent to Britain and were later interned in Frongoch. Wales.

A total of 1846 men were deported to Britain. At first they were held in a variety of prisons, but ultimately, most were transferred to Frongoch. In late August, all but about 570 of them were released. Those who remained were freed by Christmas 1916. Those in prisons, including Joe McGuinness, were released under a government amnesty in June 1917.

There were about 1500 casualties during Easter week, mostly civilians. Large areas of Dublin, including Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street) and some of the city’s iconic buildings, were either destroyed or severely damaged. The total repair bill was estimated at £2.5 million.

Long-term effects

During the rising and in its immediate aftermath, there was a lot of opposition to it, given the amount of disruption and destruction wrought on Dublin. Many in the city had family members serving in the British forces in the war and they regarded the rebel action as a betrayal. However, the executions and the speed with which they began (the first were on 3 May), were decisive in helping to change public opinion.

The rising was wrongly attributed by many to Sinn Féin, which in 1916, was a small organisation and one that had never promoted violence as a means to achieving independence. However, its ideas of abstention from the British parliament and self-sufficiency were popular and influential. In 1917, Sinn Féin was re-organised and became a major force in Irish politics. Its support grew at the expense of the Home Rule Party and by the general election of 1918, it dominated nationalist Ireland.